This post is for my students, and whoever else is interested in what DSGE theory is and why I find it useful.

Dynamic Stochastic General Equilibrium (DSGE) theory refers to a methodology employed by macroeconomists to build DSGE models -- mathematical representations of the macroeconomy. DSGE models, like all models, are used for a variety of purposes. They are used to help organize thinking. They are used to interpret data. They are used to help make conditional forecasts. They are used to predict and evaluate the possible consequences of government policies (especially useful for policies that have never been tried before). They are used to help make policy recommendations.

The use of DSGE theory is often criticized in ways that reflect what I view as a deep misunderstanding of the research program, how it fits in with the evolution of macroeconomic theory over time, and how it is actually applied by (say) central bank policy makers. This is, I think, to some extent the fault of DSGE practitioners who, accustomed to speaking in their specialized trade language, find it difficult to translate core ideas and findings in the vernacular. (This is an issue with most trade associations, of course, but is especially acute in economics because so many non-specialists take an interest in the subject.)

Let me first provide some context for my views. We are all scientists trying to understand the world around us. We use our eyes, ears and other senses to collect data, both qualitative and quantitative. We need some way to interpret/explain this data and, for this purpose, we construct theories (or hypotheses, or models, or whatever term you prefer). Mostly, these theories exist in our brains as informal "half-baked" constructs. This is not meant to be a criticism (as long as we recognize the half-baked nature of our ideas and why some humility is always in order). Often it seems we are not even aware of the implicit assumptions that are necessary to render our views valid. Ideally, we may possess a degree of higher-order awareness--e.g., as when we're aware that we may not be aware of all the assumptions we are making. It's a tricky business. Things are not always a simple as they seem. And to help organize our thinking, it is often useful to construct mathematical representations of our theories--not as a substitute, but as a

complement to the other tools in our tool kit (like basic intuition). This is a useful exercise if for no other reason than it forces us to make our assumptions explicit, at least, for a particular thought experiment. We want to make the theory transparent (at least, for those who speak the trade language) and therefore

easy to criticize. Constructive criticism is the fuel that fires the furnace of new ideas in academia. [ End of philosophical rant :) ]

Now let me turn back to DSGE theory. I think it will be useful to break the acronym into its parts and discuss each component separately.

The "D" stands for

dynamic--as in--the phenomena in question involve a time element. The opposite of dynamic is static. While static models have their uses, who's going to argue that a dynamic element isn't desirable? Almost all decisions like consumption and saving, deficit-finance, human capital investments, have a time dimension to them. No controversy here, I hope.

The "S" stands for

stochastic--as in--societies appear subject to random events, like unforeseen technological breakthroughs, unexpected changes in government policy regimes, or just random acts of nature. Again, I don't think there's much controversy with this idea. Note, however, many DSGE models do not have the S, in which case we might instead employ the acronym DGE. (For a history of the evolution of these acronyms, see

here.)

The "G" stands for

general--as in--well, it's not entirely clear. There is a traditional distinction in economics between

partial and

general equilibrium theory. The partial equilibrium approach (associated with

Alfred Marshall) refers to the supply-demand curve analysis that most people are familiar with. The analysis is "partial" in the sense that it typically restricts attention to a particular market--like the market for motor vehicles, taking the price of other goods as given. In contrast, the general equilibrium approach (associated with

Leon Walras) strives to model the economy as a closed system, paying particular attention to how markets interact with each other and how prices are determined jointly. Importantly, the "G" insists on giving an explicit account of the government budget constraint (i.e., a government is not to be modeled as

Jesus feeding the multitude.) Another way to think about "G" is that it means to capture the possibility of "feedback effects." The notion of feedback effects in macroeconomic systems is not, I do not think, controversial.

This leaves us with the "E," which stands for

equilibrium. Here lies the controversy. But why? For all sorts of reasons, some of which are based on legitimate concerns, and some of which are based on simple misunderstanding.

Let me first address the misunderstanding. The concept of "equilibrium" in economics has evolved to mean something quite specific and something quite different from the notion of a "system at rest" (which is closer to what economists label a steady-state). Technically, an equilibrium is simply a set of conditions

imposed by the theorist to help determine the outcome of an hypothetical social interaction. In this sense, an equilibrium is probably better thought of as a

solution concept. There is no unique way to specify an equilibrium solution concept. In the game theory, there is plethora of alternatives, beginning with the

Nash equilibrium. The classical theory of Walras uses the concept of a

competitive equilibrium. In my own view (probably not representative), I even think of

general disequilibrium as just another type of equilibrium concept. Every theorist

has to have a solution concept in mind when deducing the likely outcome of an hypothetical social interaction. There is no right or wrong way to specify an equilibrium concept--there are just more or less useful ways in doing so.

Another misunderstanding is that insisting on equilibrium analysis necessarily implies that one assumes markets always "clear" in the sense prices adjust to ensure supply equals demand at all times. This is understandable because many DSGE models (especially the

RBC variety) do in fact make this assumption. But, of course, there's a large class of DSGE models that do not (e.g., the

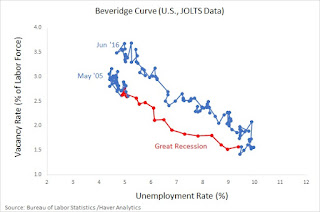

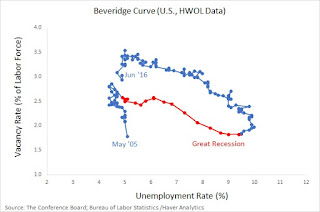

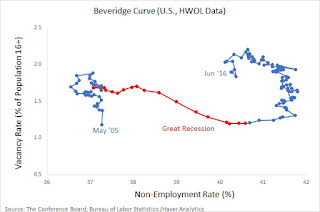

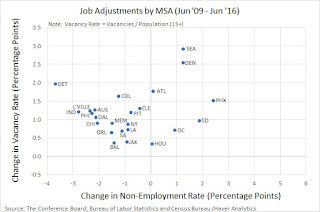

NK variety). More to the point, it's important to understand that the concept of equilibrium is not wedded to the concept of competitive market-clearing models. In DSGE models that replace centralized Walrasian markets with decentralized search markets, conventional "supply and demand" curves do not even exist. In search models, prices are determined through bilateral negotiations and the "clearing" mechanism operates through quantity variables, like labor-market tightness (the ratio of vacancies to unemployment).

A more legitimate concern relates to the equilibrium concept of "rational expectations." Because of the "D" element, the theorist

must take a stand on how expectations are formed and updated over time. Macroeconomic theorists have grappled with this question for over a century, if not longer (see

Laider, 1999). There is little controversy that people are

forward-looking. But exactly how are they forward-looking?

John Muth (1961) suggested that, in the context of a model, we might begin by assuming that our modeled agents (somehow) form

model-consistent expectations (i.e., "rational" expectations). Intuitively, the idea is that we should not model people as forming expectations that are wildly at odds with the reality unfolding around them and, that as a limiting case, we might even begin by assuming that expectations are formed in a manner that is perfectly consistent with the surrounding reality. Among other things, model agents are assumed to possess common knowledge (see,

Geanakoplos, 1992).

Now, if all of this sounds like a bit of a stretch, it no doubt is. The relevant criticism and response is recorded in section 6.4

Stationary Models and the Neglect of Learning in

Lucas and Sargent (1979). I'm not going to get into it here, but suffice it to say that there's been a large and vibrant literature on non-rational-expectations "learning" models since Lucas and Sargent wrote that piece. And you'd be very wrong to think it hasn't had any influence in the way policymakers, central bankers in particular, think about policy and its effects. St. Louis Fed president James Bullard, for example, is among those who have made significant academic contributions in this area (you can view his works

here).

In terms of their use in policy making, DSGE models are no different than their predecessors. Some applications entail large scale quantitative models to make conditional forecasts. But their main value is the manner in which they (along with other models) are used to organize thinking in policy deliberations. I think I disagree with Narayana Kocherlakota

here when he suggests that DSGE models are built purposely

not be useful for day-to-day policy making--for example, in helping to answer the question of whether the interest rate should be changed in the upcoming FOMC meeting. Instead, he views DSGE models as useful for thinking about policy rules (which I agree with). But his view here

seems inconsistent with a view he has expressed elsewhere, namely, that isolated changes in the policy rate are largely irrelevant--that what is important is how the path of interest rates is expected to evolve over time (I agree with this too). I think that the decision of whether to move rates

today has to be made in the context of what the policymaker views as wise

policy principles based on some combination of theory, evidence, and experience. These principles should no doubt make allowances for the necessity of discretionary and

ad hoc policy actions. But this allowance does not mean that reference to a DSGE model (or any other model) cannot be useful for thinking through the likely consequences of a contemporaneous policy action. [Note: I may have misunderstood the point NK was trying to make.]

In terms of a defense of the use of DSGE theory for policy, I can do no better than Chris Sims

here (video, highly recommended). See also this

interview with Tom Sargent, who defends modern macro theory. Finally, I have my own related post:

In Defense of Modern Macro Theory.